Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

No Future With Evernote

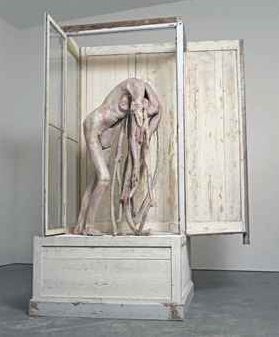

Posted in Art Education, Creating Digital History, Evernote, How To, Uncategorized, tagged BerlindeDeBruyckere, DigitalAge, DigitalTools, Mendeley, MicrosoftOneNote, OneNote, Zotero on November 24, 2015| 3 Comments »

Fashion Archives & Digital History

Posted in 20th Century, Archival Resources, Creating Digital History, Digital Archive, How To, Interesting Facts, tagged Digital Archive, digital projects, digital tools, fashion, web archiving on November 23, 2015| 3 Comments »

The creative process for large fashion corporations, from design houses to fast-fashion behemoths, is breakneck, furious and often wasteful. Fashion companies on average deliver up to eight collections a year and mass companies can churn out up to 52 “micro-seasons” a year, with new trends hitting stores weekly.[1] Season after season, week after week, ideas are generated, textiles are developed, prints and patterns are drawn, stitches, patterns and techniques are developed and samples are created. All parts of the product development life cycle are carefully detailed and documented to share with manufacturing facilities around the world. This process utilizes thousands of people and continues non-stop, every day, all year long. In order to keep deliveries on time, and ultimately, customers coming back for more, this process requires working twelve months or more in advance. And once the process of garment creation is underway there is an immediate need to market these collections.

Industry giants dedicate tens of millions of dollars a year to launch massive advertising and public relation campaigns in order to keep fashion feeling new and exciting. Like the creation of apparel, marketing also follows a relentless life cycle creating new visuals and ideas of engagement season after season. Ideas are generated, photo shoots are executed, media is bought, pictures are printed, websites designed, stores are updated, packaging created, direct mailers are delivered and the excitement continues.

How many of these ideas are actually new? How many times are garments recreated? Is fashion ever original? How many unique and innovative images and campaigns can be created year after year? Or is repetition reinvention? Are familiar designs and a recognizable aesthetic the keys to a successful brand identity and, ultimately, longevity? Does recognizing a brand’s past help build a solid future? Or does it matter at all?

My thesis is rapidly approaching and the process of research has begun. These are the questions my I will attempt to answer by exploring the value and meaning of corporate archives in today’s fashion industry. It will also take a look at principles and practices—how to build them, what the benefits are and the cultural effects they may or may not.

Creating archives for non-fashion related corporations has been well documented, dissected and debated. There are countless journals and associations related to the research and development of business archives. Many of these journals, paper and articles are going to help serve as research for my thesis. Yet despite the growing interest in creating fashion-related archives, evidenced by the number of diverse brands that have existing archives, there remains a dearth of information on the development, utilization, management of these private libraries. In addition, business and historical archiving, as well as library science are void of fashion specific information technology.

Creating Digital History has served as a wellspring of information, rich in resources and platforms that will benefit my thesis and possibly the end use of creating a real archive for my current employer. The use of Omeka as an archival tool, while not the most fluid or advanced interface, is basic and solid in its straightforward and uncomplicated user experience. I can clearly see how this could translate into a similar system for a fashion company and the development of a corporate repository. All of the information combined in this course has given me hope and confidence that a universal, yet customizable, archiving system for fashion companies can easily be developed. Now bring on my thesis!

Sources:

[1] Whitehead, Shannon. “5 Truths the Fast Fashion Industry Doesn’t Want You To Know.” Huffington Post. October 19, 2014.

Using Evernote in My GVDHA Research

Posted in Archival Resources, Creating Digital History course, GVH Exhibits, How To, tagged Evernote, Greenwich Village, Research on November 16, 2013| Leave a Comment »

Evernote is a great note taking software that really helped me both organize my research and prepare a narrative for the GVHDA web exhibit. Its flexibility – which allowed me to make “notes” of my own creation or capture full webpages, excerpts of websites, and images on websites – enabled me to keep a constantly-updating archive of materials necessary for constructing a well-researched final project.

I had never used a digital service or software for note taking before enrolling in this class. I usually rely on my Gmail account for organizing web links and drafts of my writing. Using it as a storage space ensured that my work would never be lost and that I could continually revisit resources and my own research from my cell phone, tablet, laptop, and any computer with an Internet connection.

There are, however, some problems with organizing research in my inbox. Beyond labeling each email with the name or kind of information I stored within it – “draft introduction,” for example, or “New York Times article on Second Avenue” – there is no function for sorting the information that I was keeping and creating. Websites in particular posed a problem because each email simply contained a link with no preview of the actual content. I also had trouble distinguishing between classes when using my email account, making it difficult to keep track of multiple research projects each semester.

The tags I used in my Greenwich Village Digital History Notebook.

As a result, Evernote is a welcome change in the way I conduct research and it solved all of the issues that I had with storing my work online. I can easily access it using the application that I downloaded to all of my devices or through the Evernote website on any computer. I can also sort my resources using tags of my own creation, and I have made different notebooks for the various projects that I’m working on this semester.

The most helpful aspect of Evernote is its tagging capability. As an Internet user familiar and comfortable with tagging, it is great to be able to impose a frame on and implement tags relevant to my research. After making a notebook for our Greenwich Village History class, I classified my notes into various categories. I tagged my comments on our readings and work done in class as “Class Notes.” Materials that I wanted to upload as items for the digital archive were either tagged as “Digital archive” (if I had permission to use them or they were in the public domain) or as “Digital archive?” (if I was in the process of gathering permissions and their status was still uncertain). I created my own notes containing proposals for the exhibit’s layout and drafts of exhibit pages, tagging them all as “Exhibit Planning.” Any resources that I planned to use more broadly for exhibit content were simply tagged “Research,” while more specific clippings I organized using unique tags – “CUANDO” or “Cooper” – relevant to my project.

I also really enjoyed using the Evernote clipper. It made the research process a lot easier and more efficient, allowing me to quickly save webpages, articles, and images directly to my notebook of choice. I most appreciated the tool when I was working within NYU’s subscription-based databases. A good amount of my primary source research for the exhibit was conducted in ProQuest’s historical archives, which I cannot access unless I am logged into my NYU account. Clipping the entire article webpage with Evernote, however, allowed me to view PDFs of the material, even when I was on a device or computer that was not logged into NYU.

The clipper was less helpful when I clipped Google Books resources. I usually began such searches in Google Scholar with targeted search terms that led to specific pages in books and journals. The clipper, however, is unable to “clip” the webpage so the note for any Google resource is therefore an empty page. I also had some issues immediately tagging resources while clipping. The software ran slowly when I did so and often assigned my most-used tag to the resource instead of allowing me to select the appropriate tag myself. I then needed to open the application, manually remove the incorrect tag, and reassign the material the tag I originally intended to give it. As a “free” service user, I’m limited to 60 MB of files every month. This is not an issue now – I still have 59.6 MB of space remaining before my allowance is updated – but can become problematic if I begin to rely on the service for all of my research and work-related projects.

The Case of the Missing Photographs: Finding Images from Historical Newspapers

Posted in Archival Resources, How To, Interesting Web Resources, tagged American Memory, Greenwich Village, Library of Congress, New York Times, New York Tribune, Pictorials, ProQuest, Rotogravure, World War I on October 31, 2013| 5 Comments »

Thanks to the copyright laws relating to public domain, it’s fairly easy to find newspaper articles relating to World War I on the internet. While researching the impact of World War I on Greenwich Village, for example, I found many resources in the New York Times digital archive. However, while almost all of the paper’s articles since 1851 are available online, there are very few pictures available to accompany the text. In many cases, older editions of the New York Times didn’t feature many pictures, but in some cases, they were just not included when the article was clipped and scanned. Line after line of printed words does not make for a very exciting digital archive or web exhibit, though, so I set out to find the missing newspaper photographs.

The first resource I’d like to share is one that was recommended by a classmate of mine: the ProQuest Historical Newspapers Database. This database contains scanned copies of 25 newspapers, dating back as far as the 1700s. The New York Times archives from 1851 to 2009 can be found here, just as they can on the New York Times website. Much like the New York Times archive, ProQuest allows you to view whatever pictures were clipped along with the article. However, ProQuest also gives you the option to view the article in “Page View.” This allows you to see the article in context, with all of the articles and pictures that would have surrounded it. In the regular article view there is no way to know whether an article has pictures or not without doing a lot of “guess and check.” Sometimes one article on a topic will have no pictures, while a related article right next to it on the page will have accompanying photographs. Article view, which the New York Times uses exclusively, forces you to look through every article on a given topic to find photographs. ProQuest’s page view, though, allows you to flip through the pages of a newspaper to find related articles and photos you might have missed with a simple keyword search.

There is one major disadvantage to ProQuest Historical Newspapers, though. The database is available by subscription only, which means that grad students like me can enjoy the opportunity to flip through hundreds of years of digitized newspapers, but an independent researcher would have to pay to access this collection. Also, while the pictures are easier to find than they are on the New York Times website, I still felt that there had to be a better way to find good newspaper photographs from the early 1900s.

One of the best resources that I found for these photographs is the newspaper pictorials collection in the Library of Congress’ American Memory Project. American Memory is a digital archive of items from the Library of Congress that aims to document the “nation’s memory.” It includes over 5 million photographs, documents, sound recordings and videos from colonial times through the 20th century. Some of these items are only available online through the Library of Congress and not through their creators.

The American Memory site can be browsed by topic, collection or time period, or by doing a general keyword search. In my case, it was the keyword search that turned up the best results. I searched for “27th Division,” a unit in the US Army in WWI that was welcomed home with a large parade up Fifth Avenue. The results were extensive, and very helpful. Among the long list of articles from the Army’s “Stars and Stripes” newspaper for troops, I found a New York Times result from an entire collection of newspaper pictorials. Feeling intrigued, I clicked the link to the question and a found a wealth of photographic knowledge at my fingertips!

Search results for “27th Division”- Newspaper Pictorials results are fourth, sixth and seventh on the list

Pictorial sections became popular features of American newspapers during WWI. A new process of photoengraving, known as rotogravure, meant that newspapers could produce high quality images on cheap quality paper. With Americans taking part in their first European war, rotogravure pictorials became a useful way to show the American people on the homefront the harsh realities of the war abroad. Each Sunday, the New York Times and the New York Tribune would feature a full section of rotogravure images. The New York Times also published a pictorial section in the middle of the week, and later compiled images from these sections into a book entitled The War of the Nations: Portfolio in Rotogravure Etchings. This volume included images from the mid-week pictorials published from the start of World War One in 1914 until the signing of the armistice in 1919.

The Newspaper Pictorials collection in the American Memory Project includes images from this book, as well as those from the Sunday pictorials in the New York Times and the New York Tribune. The Tribune features a number of hand-drawn images, but the Times has pages of photographs from the war and the homecoming of the troops. While the newspapers themselves are available online or on microfilm, the difficulty of properly scanning the rotogravure sections has made them difficult to obtain until now. Thanks to American Memory, though, the images can be clearly viewed online or downloaded as a PDF. Finally, I had found my missing photographs.

Oh The Places You’ll Georectify!

Posted in How To, Pastmapper, tagged digital history, digital projects, digital tools on October 29, 2013| 4 Comments »

By now, a lot of people are aware of NYPL’s fantastic digital GIS tool, Mapwarper. It enables users to create overlays with any map in their digital collection. Mapwarper has made NYPL’s geographic resources available to the public in such a way that makes them more meaningful, but it’s not the only, free-of-charge, online GIS program of its kind. In my research, I’ve explored a few others that are equally user-friendly and give you slightly different abilities, allowing you to exploit a more diverse range of resources.

Something that many people don’t know is that the Beta version of NYPL’s Mapwarper is actually still available and allows you to do one thing that the official version does not: upload and georectify maps and images that are not in the NYPL digital collection.

Downloadable Hi-Res map of New York Bay and Harbor (1903) from NOAA’s Historic Chart and Map Collection

While NYPL is a vast repository of geographic materials, there are other libraries and archives out there that house different and sometimes unique maps that a person may find more useful than what NYPL has to offer in their digital gallery. Some examples would be the Library of Congress’ Map Collection or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) Historical Map and Chart Collection. These are two repositories that allow users to search for and download high resolution files of historic maps. By going to www.mapwarper.net, instead of http://maps.nypl.org/warper, you can upload and georectify these files. And if you feel like getting creative, you can georectify literally any image file you upload, regardless of whether or not it is a map. Comme ca:

Mapwarper Beta is great for manipulating and exploring those maps you are able to download. Some digital repositories however, will allow you to look at hi-res images on their site, but have included protections so that you can’t actually download them. Gallery sales and exhibition websites, like the David Rumsey Map Collection, frequently have zoom functions to get you right up close to examine map details, but only display a small portion of the hi-res image at a time. However, there is another online program called Georeferencer that enables people to use these maps without downloading/uploading the file, using only the map’s URL. Copy and paste the link to the map into the “Georeference” field on the homepage and click “Georeference.” The hi-res data that was only available in a small box on the Gallery site, is now available as an entire image on the Georeferencer site.

British Headquarters Map overlay created in Georeferencer.org. View is from approximately W. 3rd to W. 20th Streets.

The process of adding reference points to maps and creating overlays with either of these programs is so simple that any attempt to explain it here would likely be more complicated than it should be and probably result in unnecessary confusion. It’s really as easy as clicking on the same location on two maps. It’s best to just play around with it and explore it yourself. By incorporating these other GIS programs into your research, you are able to bring in a much wider variety of resources that may otherwise have been left unexplored, and you can see what the Village was before it was the Village.

How To: Google Books Ngram Viewer

Posted in How To, Instructions, Interesting Web Resources on October 28, 2013| 3 Comments »

The Google Books Ngram Viewer is a tool that can be used to make specific searches within Google Books. Unlike searching for a single title in Google Books, using the Ngram Viewer will provide you with actual data and a graph related to your research topic. This will allow you to see a timeline of how frequently or infrequently your research subject appears in Google Books’ massive library.

I realize that this sounds a little daunting, especially for those of us (myself included) who are not statistics wizards. However, the Ngram Viewer can still be used for doing historical research, which is what I’d like to show you how to do. Read on to learn more about this interesting tool:

Comparing Flickr and Wikimedia Commons as Digital Tools for Finding Historical Images of Greenwich Village

Posted in How To, Instructions on October 28, 2013| 3 Comments »

Flickr and Wikimedia Commons (also known as Wikicommons) are very effective image search engines for the typical twenty-first century individual. I wanted to put these two websites to the test when it comes to finding useful images for a Greenwich Village historian. The theme of my own project is Anarchy and Protest in Greenwich Village During the Vietnam War Era. This was a more difficult task than I had anticipated given the goals of each of these two websites. The majority of stakeholders and active users on Flickr utilize the site to post more recent and personal photographs than historical ones. Wikicommons, on the other hand, is a fundamental online image encyclopedia that lacks depth in its collection, which will hopefully be rectified over time. The body of this blog post will go into detail about my experiences with these online image databases. The concluding paragraph will give a more general sense of how useful each website is for historians.

The names of the anarchy groups on which my project is centered skewed the results of image searches. The most critical groups are Black Mask and Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers. Black Mask returned images of tribal masks and comic book villains. Needless to say, this was not what I was hoping for. In an effort to improve my results, I added key words like “anarchy” to the search. What resulted on Flickr were mostly masks from the movie “V for Vendetta,” while there were no results on Wikicommons. Searching for images of the group Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers had slightly better returns. I believe this was because the group name is so unique. This was unlike Black Mask, which consists of more common words and thus brings with it many more times the number of results.

In discussing what I found from my search for Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers, I must first explain the group’s origin. Over the course of my research, I discovered that Black Mask and Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers were tied together. Black Mask was formed in the mid-1960s and was a very visual group. Its members were often seen protesting in public in New York City ranging in places from the Museum of Modern Art to Wall Street. Leaders of Black Mask decided to take the group underground, eliminating its publicity element, toward the end of the 1960s. The group was renamed Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers. For this very reason I expected to find very few, if any, visuals of Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers. My search for the group on Wikicommons had zero results, and suggested that I reform my search to the more censored “up against the wall motherless”. I did so just to see what would show up, and again “there were no results matching the query”. Apparently, Wikicommons just wanted me to remove the word “Motherfucker” from the search with no intention of producing better results. My search on Flickr for the group, as I briefly mentioned earlier, bore fruit. There were two Black Mask images in the results. One was a brief manifesto, and the other was a photograph from the group’s Wall Street protest. Different Flickr users uploaded these two images. The manifesto copy was even tagged “Black Mask” in addition to “Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers”, which is significant because the user who uploaded it knew the history and evolution of the New York City anarchy group. Both of these positive returns for my Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers search were Black Mask in origin, and were likely buried by tons of other images in my Black Mask search. They also were not tagged “anarchy”, which is why they did not appear in my refined search of “Black Mask anarchy group”.

Since the process had, so far, been like pulling teeth, I decided to try a different approach. My new plan of attack was twofold: I began to search for images of specific events directly relating to the groups I had researched, and more current photographs of places where such historical moments took place. This was where I had the most success with Flickr and Wikicommons.

The following were some positive examples that came from my change in approach, with some historical background: In 1967, Black Mask led a protest outside the Pentagon that turned into a violent outbreak. I found an image of a more peaceful moment on Wikicommons by searching “Black Mask Pentagon Vietnam protest”. The Weather Underground Organization (also known as the Weathermen), a group that I have not mentioned yet, had an accidental explosion while assembling bombs in the basement of a Greenwich Village townhouse. Three of the group’s members died and two escaped with serious injuries. I found an image on Wikicommons of firemen putting out the fires at the site by searching “Weathermen townhouse explosion”. Lastly, the Yippies, also being mentioned for the first time, were another radical leftist New York City group that held many public protests. One of the most famous incidents involving Yippies was at the New York Stock Exchange. Members of the group threw money from the balcony at traders on the floor. This event was blown up by the media after-the-fact, which was probably why I could not find any photographs of the event as it unfolded. I was, however, able to find recent photographs of the outside and inside of the New York Stock Exchange on Flickr.

Firemen respond to the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion at 18 West 11th Street, which was caused by the Weather Underground Organization and occurred on March 6, 1970. (Wikicommons)

The goals of Flickr and Wikicommons are different and thus pose dissimilar challenges to historians. Flickr is primarily a website for personal photographs, and is sometimes referred to as a social media website. Tangential to that, it is a hub of images of much more current people and places. Finding photographs from the 1960s on Flickr is a tall task in itself, let alone locating significant images pertaining to anarchy groups during the era. Most of the time, the best that Flickr can do for historians is present recent visuals of important sites of the past. Wikicommons, on the other hand, is more of an educational website than Flickr. Wikicommons is more useful to historians given its purpose and that its collection includes images that may serve as a sort of primary document. From my experience within the parameters of this project, neither image database provided me with much success. In the end, I would say that Wikicommons is a better historical tool to study mid-20th century Greenwich Village than Flickr.

ArchiveGrid: Discovering Accessible Archives Around You

Posted in Archival Resources, How To, Instructions, Interesting Web Resources, tagged archive, ArchiveGrid, Greenwich Village, OCLC, St. Vincent's Medical Center, World Wide Web, WorldCat on September 30, 2013| 2 Comments »

Having trouble finding archives that have the materials you need? ArchiveGrid is a great tool to use if you do not know where to begin your search! It is a free resource that allows the user access to information about different collections and finding aids that any of the participating archives have.

ArchiveGrid became a free website in 2012, allowing researchers to use its database without subscribing to it, like it had done in the past. The database contains over two million searchable archival collections. According to the about page on the ArchiveGrid website, it“provides access to detailed archival collection descriptions, making information available about historical documents, personal papers, family histories, and other archival materials. It also provides contact information for the institution where the collections are kept.”The website is designed to recognize your current location so that it can best serve your search needs. When you receive your search results, they are ranked by both closest in proximity and the hits that best fits the phrase you searched.

ArchiveGrid is supported by the Online Computer Library Center (also known as OCLC). OCLC is an organization that connects different libraries from all over the world. OCLC also manages the infamous WorldCat, the database that Bobst Library uses to make their catalogues searchable. Like OCLC, ArchiveGrid gives archives and libraries the opportunity to share their collections with the World Wide Web, allowing them to reach out to more people than they could in the past.

For my digital archive and website, I am focusing on St. Vincent’s Medical Center, once located on Greenwich Village on W. 11th Street until its close in 2010. Since this institution is no longer open, I have been searching high and low for all sorts of documents that would be relevant for my research. ArchiveGrid was one of the major tools that I have used and has directed me to different archives that I can utilize.

The ArchiveGrid search bar is at the top right where you can enter any phrase or topic that you would like to search. When I typed in “St. Vincent’s Hospital NYC,” I received 631 results.

The website divided its findings into a result list and a result summary. When you click on the “Result Overview” tab, it breaks down the results based on: people, groups, places, archives, archive locations and topics.

This is very useful when trying to narrow down the 631 matches that ArchiveGrid provided for me. You can conduct your search from here by choosing a specific topic. The results generated on the “Results Overview” helped me identify different topics about St. Vincent’s that I would like to focus on in my online exhibit. For example I can select the group “Catholic Church,” or the topic “Medicine and Health,” since St. Vincent’s was a Catholic medical center. I can also select narrow my search by the location of the archives. When I click on New York, I am left with 69 results, much smaller from my first search. The different collections range from oral histories from 9/11 victims who were treated at St. Vincent’s, to the papers of doctors or an AIDS activist videotape collection. Under each collection is a description, if available and the name of the archive that the collection is located. The researcher can than click below that the link for either contact information for the archive or the finding aid for that collection. For example, the 9/11 oral histories are located at Columbia University and I am then directed to their contact us page on their website.

From here I can browse through their collection and determine if I need to make a visit to their library. I now know that I have the ability to include information on St. Vincent’s significant role after the events of 9/11 into my exhibit as well as any information regarding the AIDS clinic that was established at St. Vincent’s.

ArchiveGrid is a great resource to use if you are looking for archives to go to without having to visit them right away and making any unnecessary trips. It also helps you to be a more efficient researcher as you can go into any archive that you find on ArchiveGrid and know exactly which collection and even which folder you are looking for. For more information on ArchiveGrid and OCLC check out their websites!

Researching the Washington Mews with Historypin

Posted in How To, Instructions, Interesting Web Resources, Uncategorized on September 30, 2013| 1 Comment »

Historypin is a free, interactive, and interesting way to perform historical research. Unlike many digital archives or resources that you may come across in your research, Historypin relies on crowd sourcing for its content. Individuals and organizations from across the globe can sign up and upload their own historical photographs and information. This interactive format (supported by a partnership with Google) provides research opportunities that may otherwise be unavailable.

The goal of Historypin is “…to help people to come together from across different generations, cultures and places, around the history of their families and neighbourhoods, improving personal relations and building stronger communities.” Its founders appear to be achieving this. There is an emphasis on shared learning and community on the website – museums, schools, and archives are all encouraged to participate. This move toward sharing information isn’t going unnoticed. Although Historypin was founded recently (its official launch was in July 2011), it has already received 287,000+ contributions from around the world.

If you want to hear about Historypin from its creators and see a neat video they made, click here. But if you’d like to follow me on my quest for researching the history of the Washington Mews, read on:

Using the Google News Archive Search to Trace the History of the Church of All Nations

Posted in Archival Resources, Creating Digital History course, How To, Interesting Facts, Interesting Web Resources on September 27, 2013| 1 Comment »

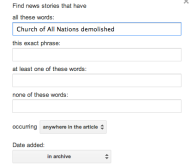

The Google News Archive Search is a great tool for conducting research on a historical topic. It was launched in 2006 as an extension of Google News, allowing Internet users to “search and explore information from historical archives dating back over 200 years.” Google partnered with The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and other newspapers as well as aggregators like LexisNexis and Thomson Gale to index both free and fee-based newsprint. In 2008, digitally scanned newspapers were added to the News Archive’s content.

The tool is incredibly easy to operate. Users can input search terms into any or all of four categories, choosing whether a search should include “all these words,” “this exact phrase,” “at least one of these words,” or “none of these words.” Any search can be restricted even further. Users can choose to limit the terms to occurring “anywhere in the article,” “in the headline of the article,” “in the body of the article,” or even “in the URL of the article.”

Because the search engine includes archived content, users can also limit a search for articles written “any time,” within the “last hour” or “last day,” in the “past week” or “past month.” Researchers interested in historical content can choose to specify dates or generally search “the archive” that Google has assembled. Users can also search for articles from a particular news source or from a specific geographic location.

Google’s News Archive Search is an especially useful tool for researchers interested in assembling a timeline for their topic. I’m currently using it to supplement my research of the Church of All Nations’ long and complex history. Secondary sources claimed, for example, that the Church officially opened in 1922. A Google News Archive Search for “The Church of All Nations” and “opened” in “1922,” however, returned with no results. When I expanded my search to all articles in “the archive” I discovered a New York Times article from a year later covering the institution’s opening ceremony on February 15, 1923.

I was also able to better determine a timeline leading up to the building’s demise in 2005 using the tool. The search terms “Church of All Nations” and “demolished” led to articles published in The Villager that document the gentrification of the Lower East Side and development pursued by AvalonBay Communities, Inc. beginning in 1999. A 2004 article, for example, profiled the community gardening advocates the Green Guerillas. In December of that year, the group petitioned Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe to protect the Liz Christy Bowery Houston Community Garden from the impending destruction of the adjacent Church building. According to an article from the New York Times, moreover, demolition of the Church of All Nations building began in April 2005.

Articles I found through Google’s News Archive Search were equally helpful in presenting other avenues for potential research. After reading through pieces from The Villager, I established that I needed to more fully explore the role of the Cooper Square Community Development Committee and Businessmen’s Association. The organization opposed the Cooper Square Urban Renewal Area project, which planned to redevelop the city from 9th Street to Delancey Street and from 2nd to 3rd Avenue inclusive of the former Church of All Nations building.

I also uncovered the names of adjacent locations, including Mars Bar and McGurk’s Suicide Hall, threatened by this redevelopment. The search similarly identified individuals influential in the early running of the Church, like Dr. Thelma Burdick and Joseph Giglia, as well as inhabitants who lived in the building in later years until it was demolished.

There are some disadvantages to using Google’s News Archive Search. While it provides a thorough search through archived newspapers, many articles cannot be accessed without paying fees. This is not an issue for students or scholars affiliated with institutions that pay for subscriptions, but independent researchers will find it difficult to access many materials for free. Researchers with undefined search terms will need to sort through pages of possible articles, moreover, before finding material appropriate to the search topic.

In 2011, Google announced that it would no longer add content to its News Archive Search or develop additional functionalities to employ while searching content that is already available on the site. Despite the end of what some have called “Google’s ambitious effort to digitize the world’s newspaper archives,” the News Archive Search remains an essential tool for historians interested in finding out how a research topic is covered in newspapers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.