The Hulk passes through Washington Square Park in The Amazing Spider-Man, issue 381, 1993

Ta-Nehisi Coates hit the nail on the head when he said, “Comics are so often seen as the province of white geeky nerds. But, more broadly, comics are the literature of outcasts, of pariahs, of Jews, of gays, of blacks. It’s really no mistake that we saw ourselves in Doom, Magneto or Rogue.” Since their inception, comic books have been a place for fantasy, wish fulfillment and political commentary. Much like science fiction, a genre decades old by the time comic books became popular in the United States, comic books often reflected the fringes of American society. They told the stories of outcasts and aliens, people who didn’t step in time with the rest of humanity. It’s unsurprising that someone like William Moulton Marston, psychologist and creator of Wonder Woman, would find himself so drawn to the medium.

This phenomenal development of a national comics addiction puzzles professional educators and leaves the literary critics gasping. Comics scorn finesse, thereby incurring the wrath of linguistic adepts. They defy the limits of accepted fact and convention, thus amortizing to apoplexy the ossified arteries of routine thought. But by these very tokens the picture-story fantasy cuts loose the hampering debris of art and artifice and touches the tender spots of universal human desires and aspirations, hidden customarily beneath long accumulated protective coverings of indirection and disguise. Comics speak, without qualm or sophistication, to the innermost ears of the wishful self.”

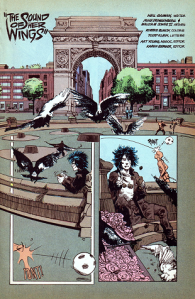

Front page to The Sound of Her Wings from Sandman: Preludes & Nocturnes, Issue 8, 1991.

Marston wrote this for a 1943 issue of The American Scholar, a year after Wonder Woman debuted in her first solo book, Sensation Comics. He was a blacklisted psychologist who lived in a polyamorous relationship with two women, Olive Byrne and Elizabeth Holloway. All three worked, wrote and helped raise their four children. A self-identified feminist, Marston infused Wonder Woman with his politics, hoping to create a new feminine ideal. Perhaps, then, it is even less surprising that Marston’s inspiration was found largely in the radical communities of Greenwich Village.

Wonder Woman was not the only superhero to have passed through the Village. Comic book writers and artists have been sending their characters to the quintessential home of radical counterculture for decades. Wonder Woman herself lived in the Village in the sixties and seventies. Madame Xanadu, a sorceress based on the Arthurian legend of Nimue, had her salon on Chrystie Street. Peter Parker, that most relatable of high school geeks and New York native, swung through the Village regularly. Kyle Radnor, one of the iterations of the Green Lantern, was an artist whose studio was in a Greenwich Village loft. It made sense to place these characters here. Like the folk music that permeated the Village in the 1950’s and 60’s, comic books told stories that were always meant for the common person, but also for those who didn’t quite feel like they were in sync with the rest of the world. People found shelter in the Village, and it was no different on the pages of

Spider-Man or

Wonder Woman.

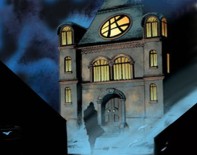

A shadowy figure approaches the Sanctum Sanctorum, home of Doctor Stephen Strange, which first appeared in Strange Tales, issue 116, 1951. The Sanctum existed in multiple dimensions, but the front door was on Bleecker Street.

Outside comic books, Greenwich Village was home to people like socialist writer

Max Eastman, who published

Child of the Amazons and Other Poems in 1913.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman published

Herland, a utopian novel about an egalitarian world without men, in her magazine

Forerunner in 1915. Clearly Amazonian society had been on the minds of many Village feminists, not just Martson’s.

Because of their format, and their intended audiences, comic book creators had room to do the daring, to challenge social mores. Sometimes they didn’t succeed, and often they ended up just reproducing the same prejudices they were attempting to subvert. Despite the efforts of people like Marston, the comic book industry has been dominated by white men, its path dictated by what they think their audience of white teenage males want to see. But comic books still have their roots in counterculture, and are so identified with bohemian Greenwich Village that author

Michael Chabon set much of his novel,

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, there. His characters, Joe, Sammy and Rosa, called the Village home, often finding refuge there through a storm of homophobia, sexism and anti-semitism.

Supergirl is sent to the Village to speak to Madame Xanadu in Wonder Woman, issue 292, 1982

Comic books have certainly changed over the years, and so has the Village, but their shared history continues to draw people for similar reasons. They have the ability to show us our fantasies and desires, reflecting them back to us for better or worse. Idealists, radicals, outcasts and sometimes just lonely kids looking for companionship – those are the people who still hold comic books closest, and comic book creators owe much of that to the influence of the Village.

Related Reading:

Gaiman, Neil. Sandman: Preludes & Nocturnes. New York: DC Comics, 1991.

Chabon, Michael. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. New York: Random House Publishing, 2000.

Daniels, Les. Wonder Woman: The Life and Times of the Amazon Princess: The Complete Story. San Francisco: Titan Books, 2000.

Schwartz, Judith. Radical Feminists of Heterodoxy: Greenwich Village 1912-1940. Norwich, Vermont: New Victoria Publishers, 1986.

Read Full Post »

You must be logged in to post a comment.