by Stephanie Krom, Kerry Heimer, and Salome Jeronimo

The PastMapper platform that Brad Thompson has created for the 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940 census data of West 9th Street in Greenwich Village is visually quite different from the prototype map he created compiling the city directory entries of San Francisco from 1852-1853. The San Francisco city directory map displays data through the use of colored markers distinguishing between residential and business locations. The West 9th Street census data map, on the other hand, with most if not all entries being residential, simply offers outlines of each building structure. The only color difference on the West 9th Street map comes from the different decades that are represented on the block.

When clicking on the colored markers in San Francisco, a small pop-up appears offering the address of the particular location along with the name of the resident or business present there in 1852-1853. The West 9th Street data shows a progression in the platform, including the race, sex, age, and occupations of the recorded residents. This inclusion of additional information offers a more complete and useful representation of the individuals living in the area, as well as the changing social and architectural landscape over time.

Of particular interest, and something not included in the San Francisco data, is the information specific to the buildings that is offered for West 9th Street. When clicked on, each listing provides the name of the building, the year it was built, the names of the builders and architects, and the list of residents. Knowing the date of the building’s erection and name of the architect is a particularly useful tool in finding out which buildings still stand today. For example, The Portsmouth is a building at 38-40 West 9th Street that was built in 1882 by architect Ralph Townsend in the Queen Anne style that was popular in America during the late nineteenth century. Today, the Portsmouth remains an apartment building on this scenic block in the Greenwich Village Historic District. PastMapper offers that, in 1910, a few decades after the Portsmouth was built, the building was home to at least sixty residents, ranging from white nuclear families with no servants to larger white families with several live-in servants. The professions listed for many of the 1910 residents of The Portsmouth, including lawyer, physician, and engineer, and the presence of many servants within the building indicate that the primary families in this building during the early-twentieth century were of the upper classes of New York society. This information is interesting particularly when compared to the people who live in The Portsmouth today. In many ways, the people of The Portsmouth have stayed the same – although there are no more “servants,” the families of The Portsmouth are certainly of the upper class. A three-bedroom apartment in The Portsmouth recently sold for $1,800,000.

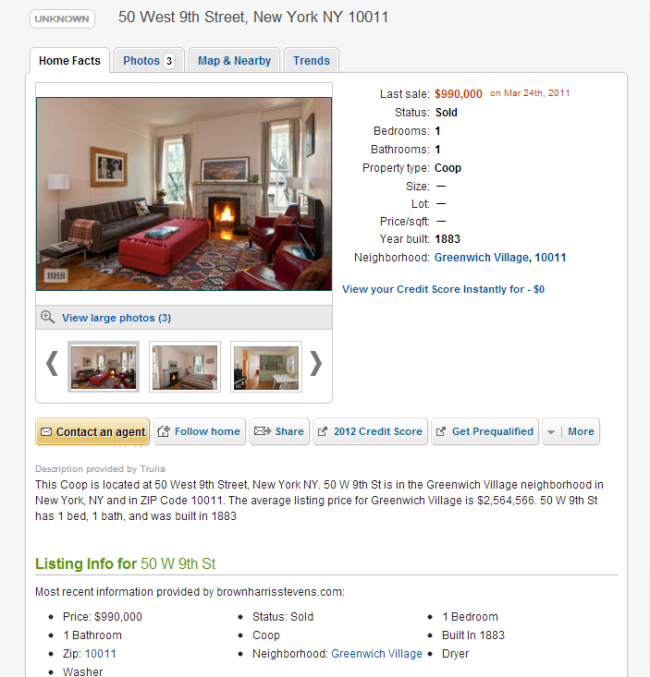

The real estate listing for unit 10 of The Portsmouth, which sold for $1.8 mil.

Courtesy Douglas Elliman

Another building constructed by Ralph Townsend in the 1880s was The Hampshire, located at 46-50 West 9th St between Sixth and Fifth Avenues, just one building away from The Portsmouth. The Hampshire is described as a Victorian style apartment building with terra cotta spandrels. Interestingly, the building was once the home of novelist Dawn Powell. The building is still an apartment building and is labeled as a Co-Op. At the time of the 1920s census, the flats on West 9th Street were occupied by upper-class working professionals. Some of the census participants in The Hampshire listed their occupations as “nurse,” “broker,” “judge,” and “editor.” According to current apartment listings, the average apartment in Greenwich Village is around 2.2 million dollars. A one bedroom apartment in the Hampshire is currently listed at 1.1 million dollars. A one-bedroom apartment in this building sold in 2011 for $990,000.

This Greenwich Village census data project offers an indication of PastMapper’s ongoing and potential development as a resource for historical research. The use of the PastMapper platform as a tool for real estate history research may indicate that, in the future, PastMapper will be used by a variety of users, from scholars to apartment-hunters.

You must be logged in to post a comment.